Download the Twitter app

Sent from my iPhone

| worm on a string (@rieuIe) |

cus a few friends didnt know this cheat yet pic.twitter.com/ttgYpzrAkG | |

| GurdjieffWork (@GurdjieffWork) |

Real art is knowledge not talent. ~ #Gurdjieff | |

| Muddy Colors (@muddycolors) |

New post on muddycolors.com // Dorien Iten: Accuracy Training pic.twitter.com/ZznF9f83oG | |

| History In Pictures (@HistoryInPix) |

Picasso's self-portrait at ages 18, 25, and 90. pic.twitter.com/MKmbGgywqy | |

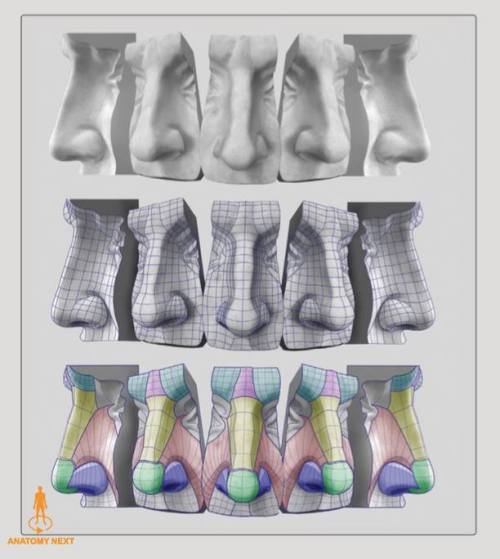

Michelangelo David's Nose by Anatomy Next

| Colleen Doran (@ColleenDoran) |

BTW the only known photo of JC Leyendecker's model and lover Charles Beach. Sorry can't recall where I pinched this. pic.twitter.com/GC5hP2Aj2y | |

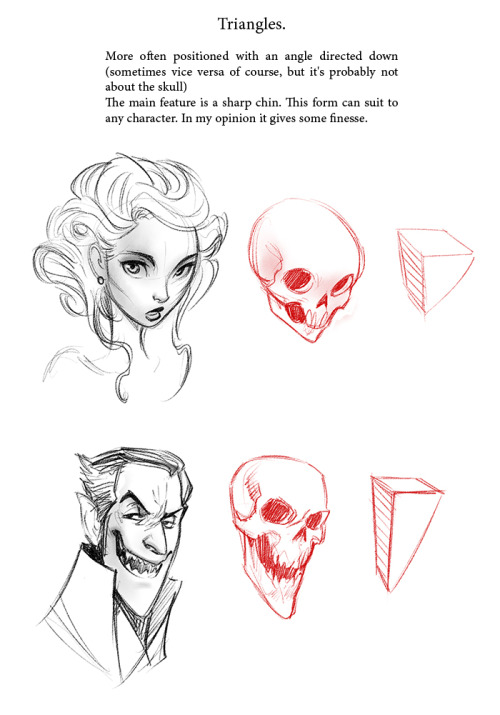

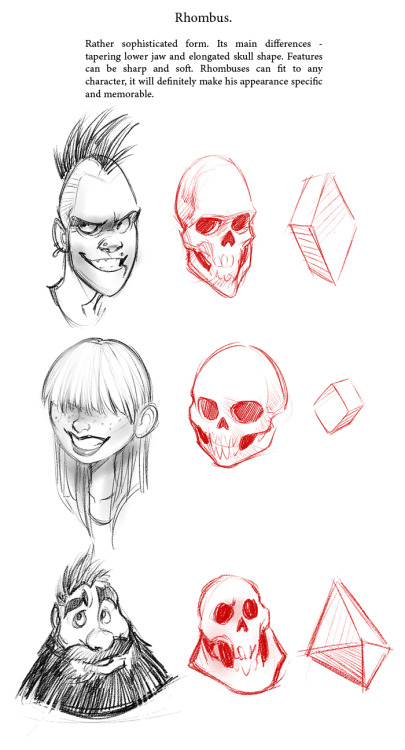

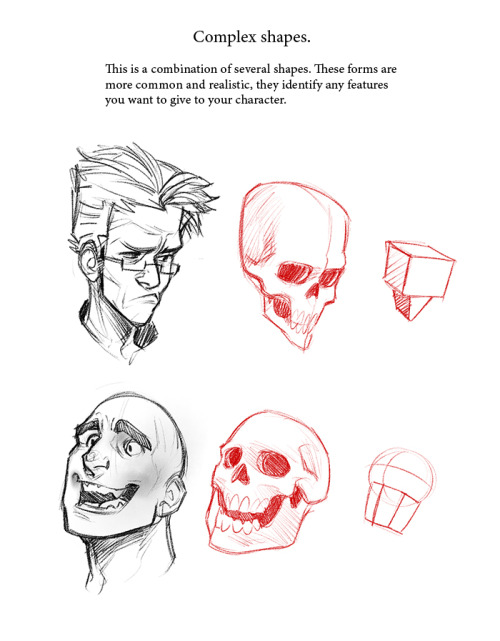

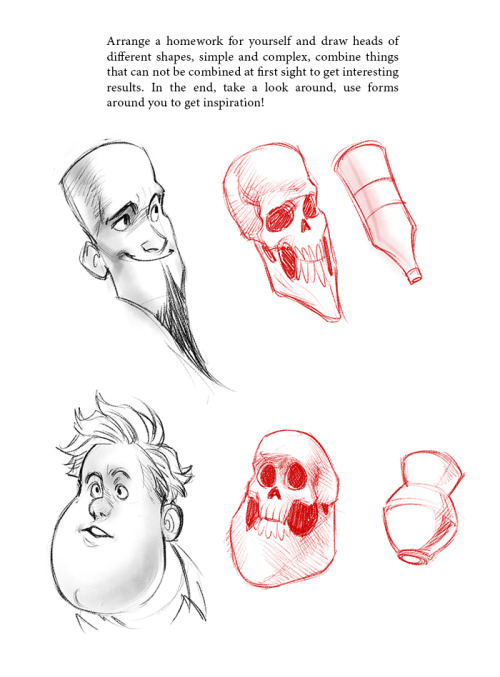

My old tutorial! Wanna share it with you)

|

| Third Place, Illusion of the Year, 2009 |

| Renae De Liz (@RenaeDeLiz) |

Q: As an artist, what can I consider if I want to de-objectify & add power to female characters? Tips in this thread pic.twitter.com/DEKF1p6YFd | |

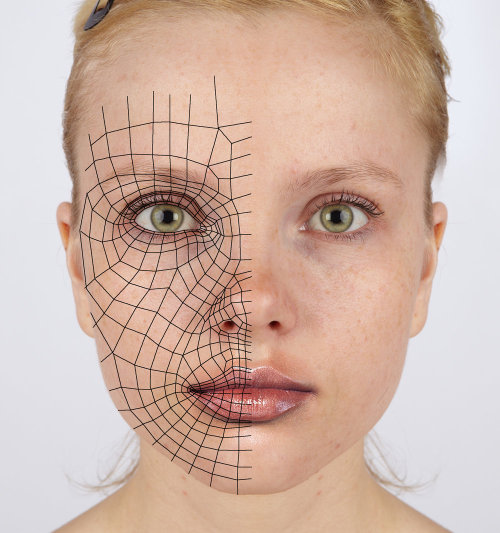

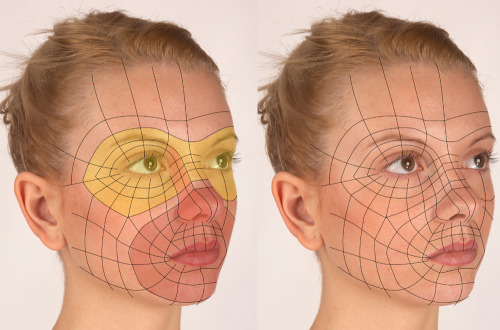

3d reference - face loops by Athey

"There is a lot of Michelangelo in that fellow," observed realist author and playwright Honoré Balzac in reference to Honoré Daumier. As one of the well-known artists of the French Realism Movement, an era of artists who honed in on real life often featuring commoners and laborers as their subjects, Daumier captured the moments of the time on a variety of mediums, including painting, lithography, sculpture, satirical cartoons and caricatures.

Honoré Daumier, Voyageurs appréciant de moins en moins les wagons de troisième classe…, French, 1808 – 1879, published 1856, lithograph on wove paper, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Image from National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art's Lorenz Eitner notes that his body of work highlights "the characteristic look and demeanor of every segment of Parisian society, ranging from the crotchets and timidities of the urban middle class with which he fondly empathized (Les Bons Bourgeois), to the frauds of speculators (Robert Macaire), the pomposities of lawyers (Gens de justice), the self-delusions of artists, the rapacity of landlords, and the vanity of bluestockings. " His abhorrence for lawyers appears to stem from his early employment as an errand boy for attorneys. He also paid particular attention to King Louise-Phillipe, which eventually provoked the sovereign to sentence Daumier to jail for six months due to the harshness of Daumier's wit in the satirical cartoon of the king.

Honoré Daumier (French, 1808 – 1879 ), Les Tritons de la Seine, 1864, lithograph, Rosenwald Collection 1943.3.3205

From the National Gallery of Art

His 40-year career creating satirical cartoons was chronicled in the French journals, La Silhouette, La Caricature and Le Charivari. His ascent into cartooning stems from the help of a family friend, Alexandre Lenoir, who provided Daumier informal training in drawing since Daumier's family couldn't afford to send him to art school. After copying Lenoir's art collection and the works from the Louvre, Daumier landed a fortunate apprenticeship with a lithographer who taught Daumier the technical aspects of printmaking. From there, the publisher of La Silhouette, La Caricature and Le Charivari hired Daumier around 1829 to be a cartoonist for the satirical publications.

Honoré Daumier (French, 1808 – 1879 ), Un Abus de confiance, 1842, lithograph on newsprint, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund 1979.49.105 From the National Gallery of Art

Honoré Daumier (French, 1808 – 1879 ), Des gens dont le soleil réjouit peu la vue, 1855, lithograph, Rosenwald Collection 1958.8.64 From the National Gallery of Art

Honoré Daumier (French, 1808 – 1879 ), Le Tondeur de chiens, 1842, lithograph on newsprint, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund 1979.49.40 From the National Gallery of Art

Honoré Daumier (French, 1808 – 1879 ), Ce que certains journaux appeleraient…, 1870, lithograph, Rosenwald Collection 1943.3.3207 From the National Gallery of Art

Honoré Daumier (French, 1808 – 1879 ), Daumier fut le peintre ordinaire…, probably 1839, lithograph on newsprint, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund 1979.49.254

If you enjoyed this brief history on the realism artist, Honoré Daumier, and would like to dive more into art history, check out the History of Art course on HOW Design University. You'll explore art history from a broad thematic perspective, looking at art through the lens of nature, the human body, society, religion, and politics. Engaging lectures and projects will challenge you to research and analyze the artists that interest you, opening up new channels of inspiration for your work.

The post Honoré Daumier: The Michelangelo of Caricature appeared first on Print Magazine.

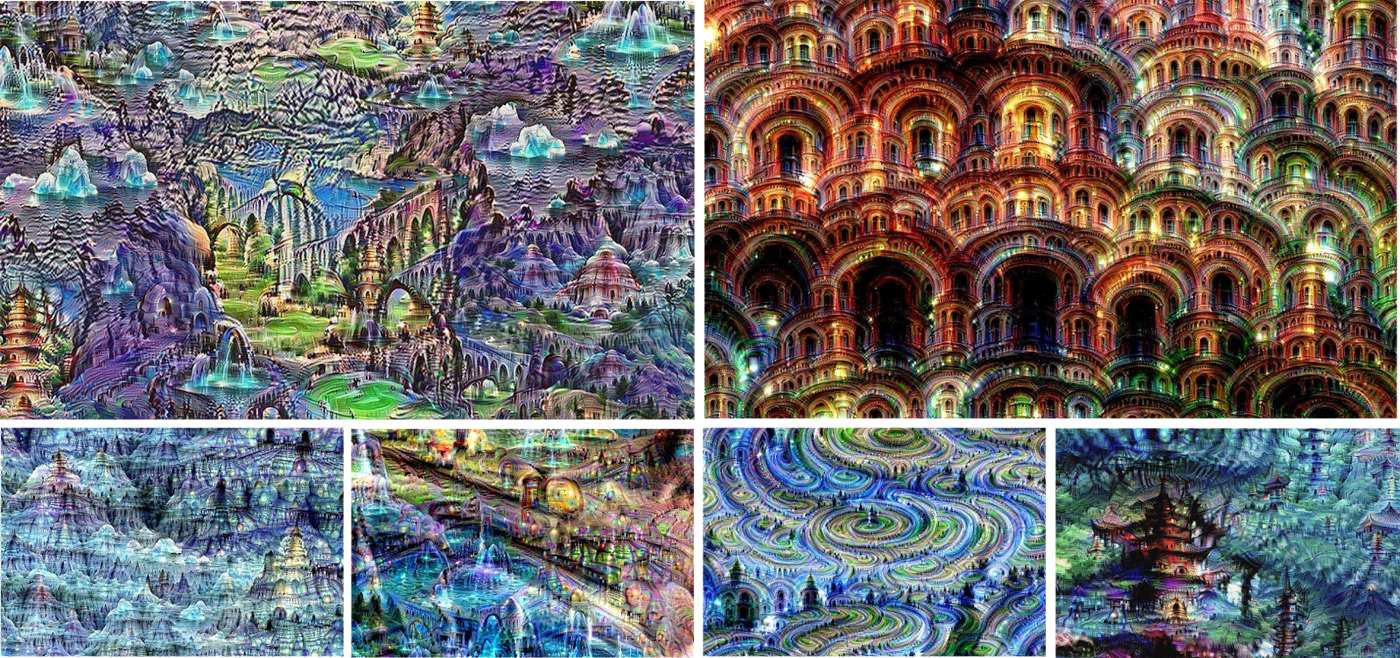

Google doesn't just want to dabble in using AI to create art -- it wants you to make that art yourself. As promised, the search giant has launched its Magenta project to give artists tools for bringing machine learning to their creations. The initial effort focuses around an open source infrastructure for producing audio and video that, ideally, heads off in unexpected directions while maintaining the better traits of human-made art.

Ultimately, Google doesn't just want the technology to produce 'optimal' art based on what it learns from samples. It's hoping for the same imbalance (that is, focusing on one element over others), surprise and long-term narratives that you see in people-powered projects. It should feel like there's a distinct personality to a song or video.

You can look at Google's early Magenta code right now, and the company is vowing to accept both code and blog posts from outsiders who have something to add. If enough people rally around the idea, you could see a budding community of artists who add AI flourishes to their productions.

By Paul Leveille

The features are what make human faces so interesting. Although most features are constructed similarly from person to person, each individual still exhibits subtle and not so subtle differences. For example, each nose has a bridge followed by cartilage and two nostrils, but some noses are thin while others are broad; some are turned up and others are hooked; and so on.

Here I'll explain the basic structures of the nose and how to draw them.

One of the most distinctive features of the human head is the nose. It protrudes more than any other feature and gives the face depth and character. Although the variety of nose shapes seems endless, all noses have the same basic triangular form: narrow at the top, and wider and fuller at the bottom.

The upper part of the nose, the bridge, is formed by bone. The lower part consists of five pieces of cartilage: Two pieces make up the tip, two make up the wings of the nostrils, and one divides the nostrils. (See The Structure of the Nose, A.)

A Seen from below, the five pieces of cartilage that make up the lower part of the nose are apparent. The nostrils are closer together toward the tip of the nose and get farther apart toward the cheeks.

B The skin lies smoothly over the bone of the upper nose, usually catching a highlight. Highlights on the tip of the nose will make it appear to come forward.

C Drawing the nose at different and unusual angles will help you understand its shape.

D Though there are all kinds of nose shapes, all noses are basically thinner and narrower at the bridge and fuller at the bottom. Some even have a ball- or bulb-shape at the bottom.

1. When first drawing the nose, simplify it into a wedge-shaped series of planes.

2. To define the subtle shapes of bone and cartilage within the wedge shapes, start to draw the rounded forms of the bridge, the tip of the nose and the nostrils. Notice how the bulb part of the nose tapers into the bridge.

3.Continue by rendering the light and dark areas. Save the white of your paper for the highlights, or lift them out with an eraser.

Paul Leveille paints portraits of nationally and internationally distinguished clients and also conducts portrait painting workshops and demonstrations around the country. He lives in western Massachusetts. See his website at www.paulleveillestudio.com.

This article is excerpted from his book, Drawing Expressive Portraits, © 2001 by Paul Leveille, used with permission from North Light Books, an imprint of F+W Media Inc. Visit your local bookseller, call 800/258-0929 or go to www.northlightshop.com to obtain a copy.

The post Drawing the Nose appeared first on Artist's Network.

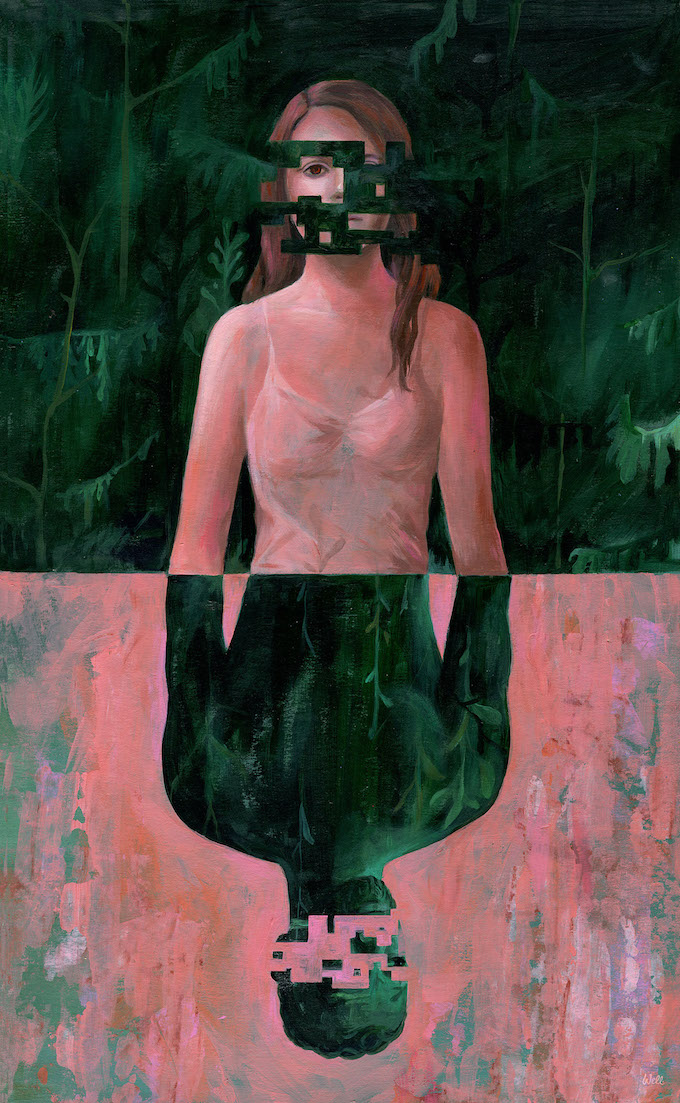

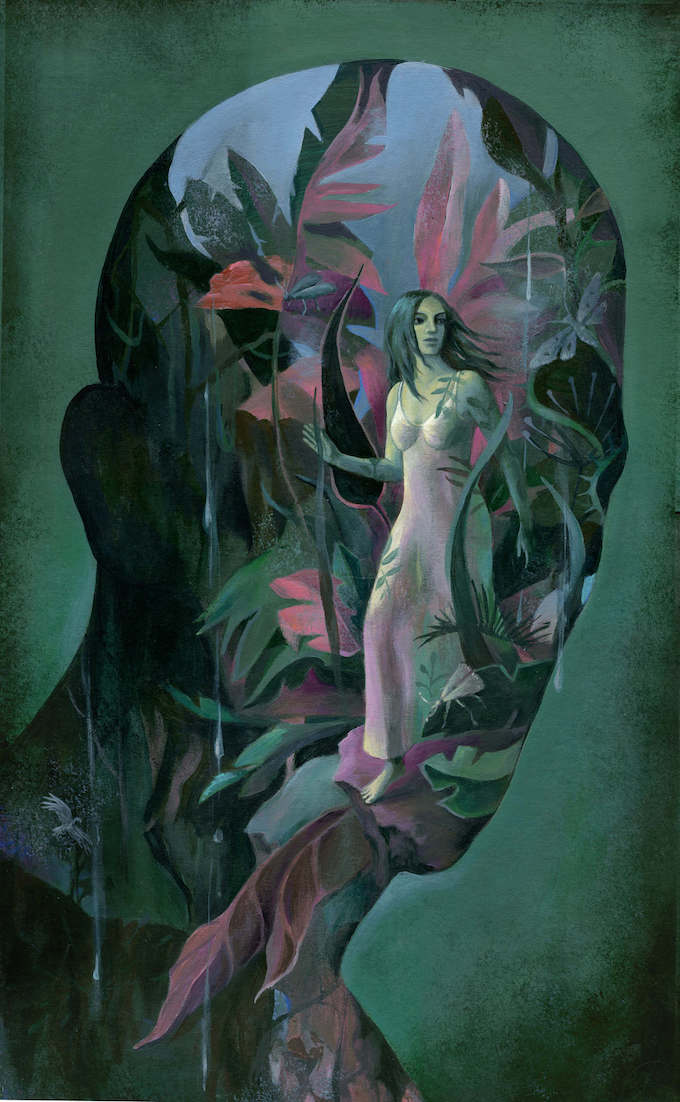

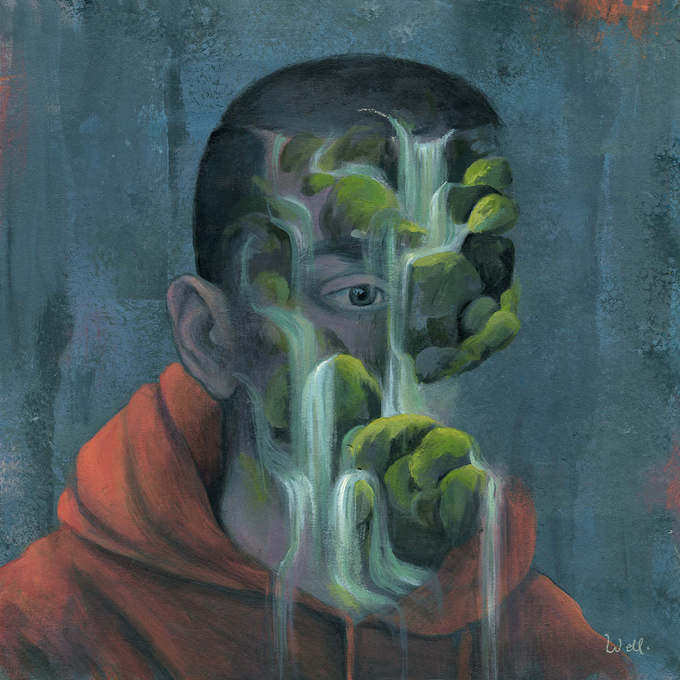

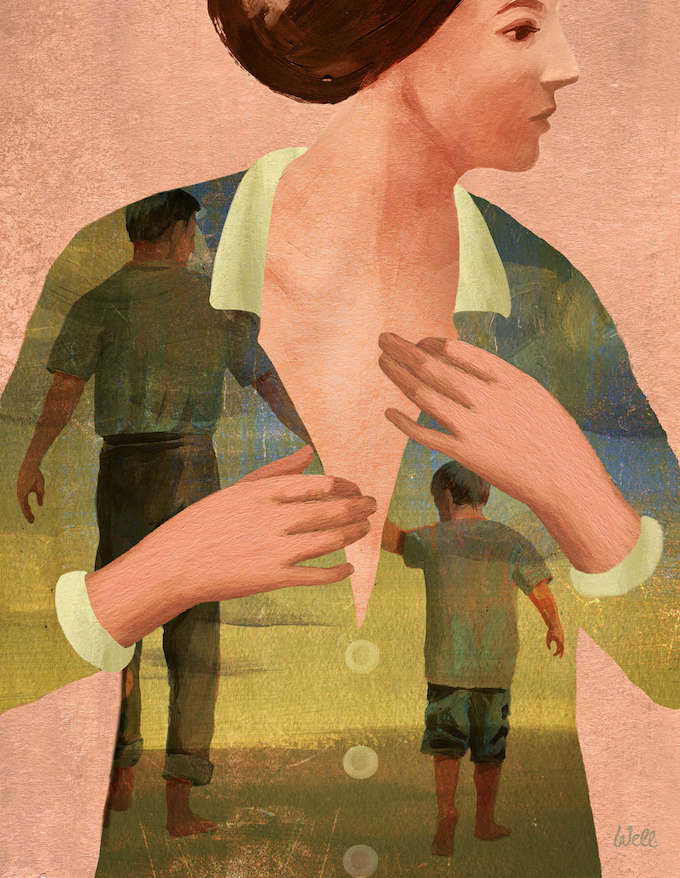

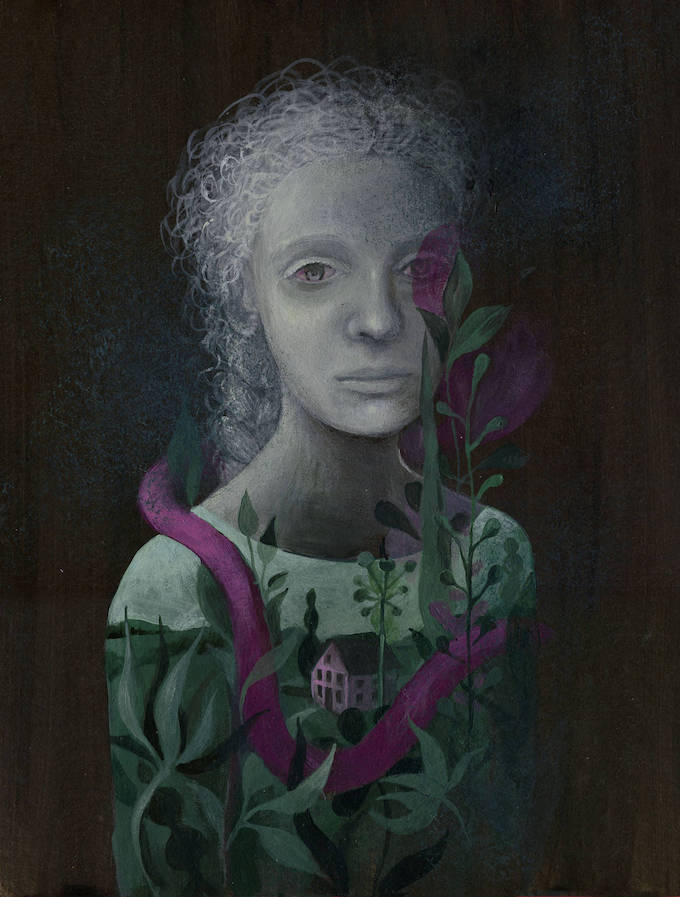

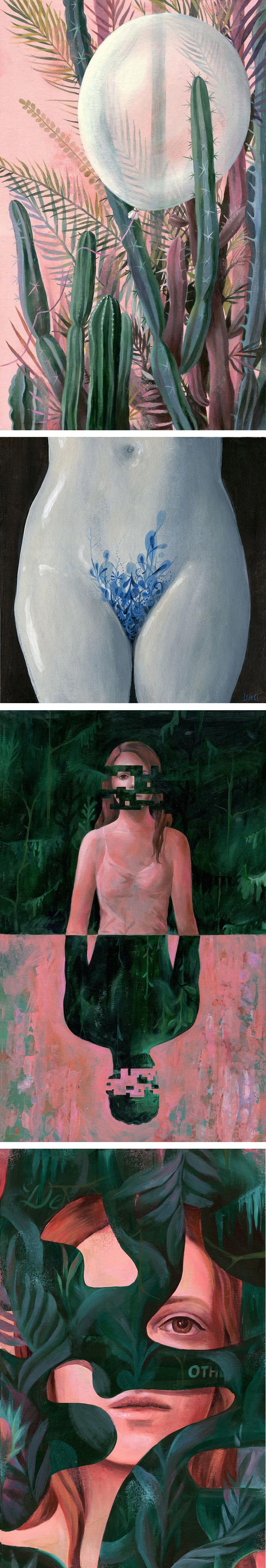

Artist and illustrator Alice Wellinger creates surreal imagery that deals with the troubles of daily life and of childhood memories. Her realistic approach to these figures and accompanying subjects has a eerie effect—it's as if they actually exist, but in a way that's similar to a vivid dream. Did these things really happen or was it just a figment of your imagination?

Her conceptual—and often, thematically dark—work lends itself well to things that aren't so cheery. Most recently, she created a series of illustrations about Shakespeare's famous tragedy, Othello.

The post Tension and Tragedy: Beautifully Haunting Works by Alice Wellinger appeared first on Brown Paper Bag.